Pendulum Measurements

Another method by which we can measure the acceleration due to gravity is to observe the oscillation of a pendulum, such as that found on a grandfather clock. Contrary to popular belief, Galileo Galilei made his famous gravity observations using a pendulum, not by dropping objects from the Leaning Tower of Pisa.

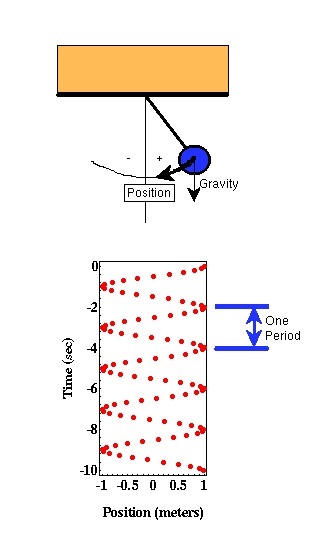

If we were to construct a simple pendulum by hanging a mass from a rod and then displace the mass from vertical, the pendulum would begin to oscillate about the vertical in a regular fashion. The relevant parameter that describes this oscillation is known as the period* of oscillation.

The reason that the pendulum oscillates about the vertical is that if the pendulum is displaced, the force of gravity pulls down on the pendulum. The pendulum begins to move downward. When the pendulum reaches vertical it can't stop instantaneously. The pendulum continues past the vertical and upward in the opposite direction. The force of gravity slows it down until it eventually stops and begins to fall again. If there is no friction where the pendulum is attached to the ceiling and there is no wind resistance to the motion of the pendulum, this would continue forever.

Because it is the force of gravity that produces the oscillation, one might expect the period of oscillation to differ for differing values of gravity. In particular, if the force of gravity is small, there is less force pulling the pendulum downward, the pendulum moves more slowly toward vertical, and the observed period of oscillation becomes longer. Thus, by measuring the period of oscillation of a pendulum, we can estimate the gravitational force or acceleration.

It can be shown that the period of oscillation of the pendulum, T, is proportional to one over the square root of the gravitational acceleration, g. The constant of proportionality, k, depends on the physical characteristics of the pendulum such as its length and the distribution of mass about the pendulum's pivot point.

Like the falling body experiment described previously, it seems like it should be easy to determine the gravitational acceleration by measuring the period of oscillation. Unfortunately, to be able to measure the acceleration to 1 part in 50 million requires a very accurate estimate of the instrument constant k. K cannot be determined accurately enough to do this.

All is not lost, however. We could measure the period of oscillation of a given pendulum at two different locations. Although we can not estimate k accurately enough to allow us to determine the gravitational acceleration at either of these locations because we have used the same pendulum at the two locations, we can estimate the variation in gravitational acceleration at the two locations quite accurately without knowing k.

The small variations in pendulum period that we need to observe can be estimated by allowing the pendulum to oscillate for a long time, counting the number of oscillations, and dividing the time of oscillation by the number of oscillations. The longer you allow the pendulum to oscillate, the more accurate your estimate of pendulum period will be. This is essentially a form of averaging. The longer the pendulum oscillates, the more periods over which you are averaging to get your estimate of pendulum period, and the better your estimate of the average period of pendulum oscillation.

In the past, pendulum measurements were used extensively to map the variation in gravitational acceleration around the globe. Because it can take up to an hour to observe enough oscillations of the pendulum to accurately determine its period, this surveying technique has been largely supplanted by the mass on spring measurements described next.

*The period of oscillation is the time required for the pendulum to complete one cycle in its motion. This can be determined by measuring the time required for the pendulum to reoccupy a given position. In the example shown to the left, the period of oscillation of the pendulum is approximately two seconds.

Gravity

- Overviewpg 12

- -Temporal Based Variations-

- Instrument Driftpg 13

- Tidespg 14

- A Correction Strategy for Instrument Drift and Tidespg 15

- Tidal and Drift Corrections: A Field Procedurepg 16

- Tidal and Drift Corrections: Data Reductionpg 17

- -Spatial Based Variations-

- Latitude Dependent Changes in Gravitational Accelerationpg 18

- Correcting for Latitude Dependent Changespg 19

- Vari. in Gravitational Acceleration Due to Changes in Elevationpg 20

- Accounting for Elevation Vari.: The Free-Air Correctionpg 21

- Variations in Gravity Due to Excess Masspg 22

- Correcting for Excess Mass: The Bouguer Slab Correctionpg 23

- Vari. in Gravity Due to Nearby Topographypg 24

- Terrain Correctionspg 25

- Summary of Gravity Typespg 26